“Trump is gonna deport you!”

“Stupid beaner.”

“Y’all are lucky to be in this country.”

The roars surging from a swarming mob growing louder and louder. A mob of White, Black and Latino.

Tony Gonzalez was inside the Oviatt Library at California State University, Northridge, watching an award ceremony when three protesters – picket signs held high – began their chant. “Trump is a great president,” they called out.

Police, present for the event, mulled over to the three protesters and asked them to leave.

Tony had been a progressive Democrat for as long as he could remember, but that day, seeing the hypocrisy of those who claimed to be victims of oppressive systems, oppressing dissenters, he went hard right. Leading the Mexican-Guatemalan to take a zero tolerance stance on illegal immigration.

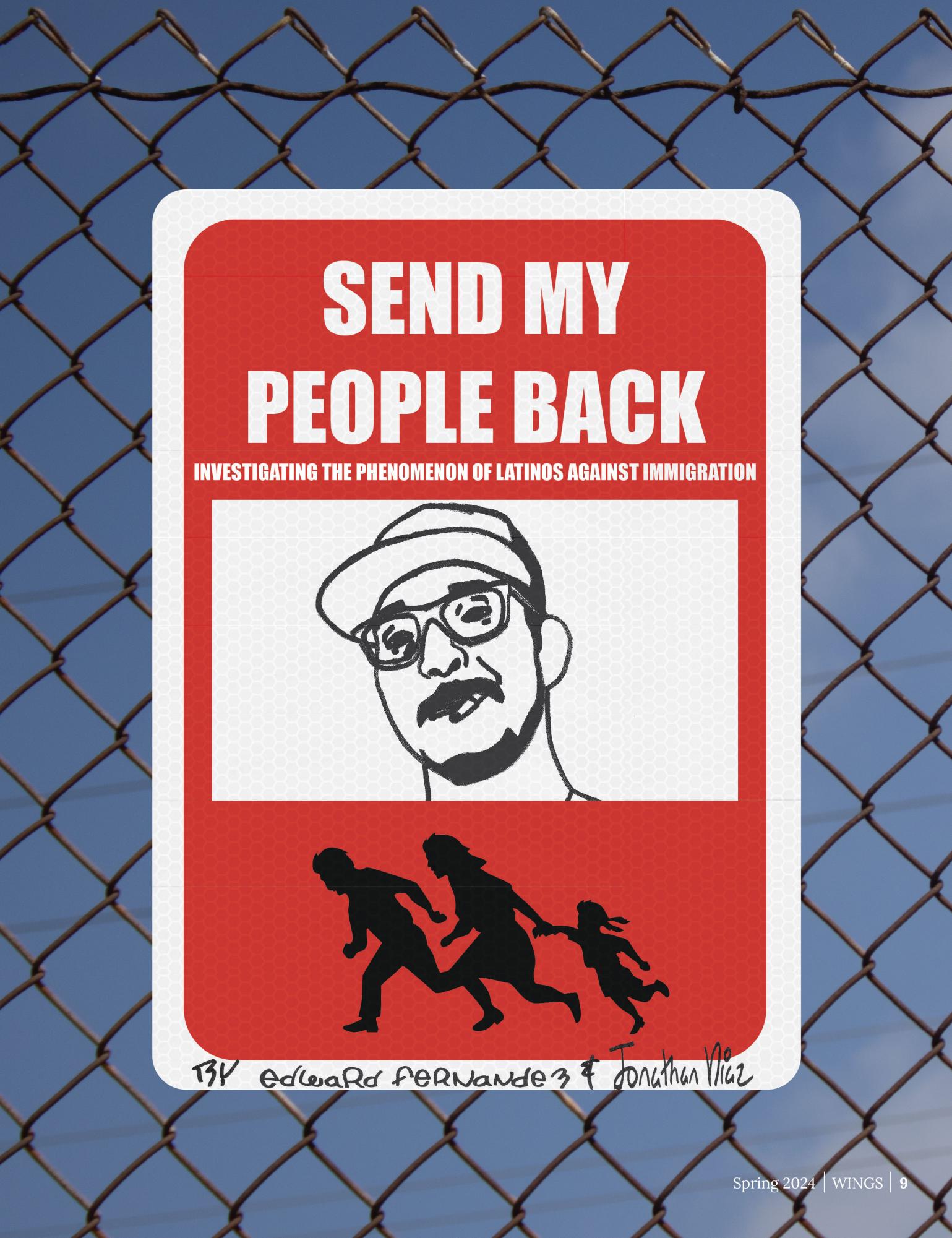

Gonzalez is just one in a growing number of Latinos opposing illegal immigration, which has become a hot button issue as Americans head into a divisive 2024 election.

Gustavo Arellano of the Los Angeles Times cites a Public Policy Institute of California survey conducted in 2019 where 75% of Latinos thought illegal immigration was a “serious problem.”

A poll conducted in January by the UC Berkeley Institute of Governmental Studies, in conjunction with the Times, found that 63% of California Latinos thought undocumented immigrants were burdensome.

John Macias, who teaches the history of Mexican and Latino Americans in the United States at Cerritos College, notes that negative sentiments come in waves historically.

Our economy depends on cheap migrant labor and, “When the economy starts to grow and prosper, usually immigration increases at the same level, but then when the economy starts to falter, then you have the anti-immigrant rhetoric that starts to increase.”

“They’re taking our jobs!”

Simple, yet effective at pointing out the competition for resources particularly among the Latino community.

Having invested a certain amount of time into the country, one might feel entitled to judge who makes a deserving migrant “And unfortunate to say, sometimes race plays a role. Migrants who are coming from different parts of Latin America, may not necessarily be on the same color line or even the same economic level in their home countries,” Macias noted.

Tony has his own ideas on what makes a deserving migrant.

“If you’re Latino, you have about a one in four chance [of growing up without a father]. We know that boys who grow up without a father are more likely to be poor, more likely to underperform in school,” Tony cited with all irony, former President Barack Obama.

This was the fate of his own father, but he beat the odds and became a mechanical engineer.

His mother grew up wearing third hand clothes, being beaten almost daily by her alcoholic father before he walked out of her life. She was told she’d never amount to anything. Now she’s a registered nurse.

Immigrant households are full of underdog stories like these.

Generations of migrants overcoming language barriers, racism and extreme poverty to make something of themselves.

Though once enough time has elapsed and all their hard work settles in, some may look upon incoming migrants without recognizing the same struggle they once went through.

If they made it, how come these newcomers can’t?

Tony’s grandmother spent 16 long years waiting to finally get her citizenship, while others crossed the border illegally.

“Deport all of them!” He pounded with his fist, “I understand that they’re trying to get a better life, but you have to do things the right way.”

He would later go on to admit that his grandmother entered the U.S. illegally.

Pulling yourself up by the bootstraps is what the American Dream is all about. The proof is in the Gonzalez family success stories. Yet it’s become a hyper fixation to the point new arrivals are being judged for their lack of achievements.

Yet despite two prestigious careers, the Gonzalez family still faces some financial difficulty.

To have achieved so much and be effectively told by your country to “shut up and be grateful for what you have” is the logical conclusion of such a hyper fixation.

To Tony, the solution for the migrant problem lies in the model set by the Bracero program.

Ship in Latinos to work the labor jobs in the U.S. then ship them right back out at the workday’s end.

Such a program isn’t enough for Antonio Vargas, who was highlighted by the Washington Post in 2001, “Don’t make us guest workers. Make us citizens. We’ve earned it.”

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection encountered over 2.4 million undocumented migrants throughout the 2023 fiscal year alone.

All having left their homes with nothing in their pockets for a myriad of reasons. All striving for the American Dream: success in their new home and assimilation, to be treated with dignity and respect by their peers despite the differences.

But assimilation is hard when your own people want you out.

“I could care less [about being isolated from the Latino community.]” Tony rationalized, “I could get along with other ethnicities.”

People can be very close-minded, he said.